What Was Gies Motivation for Helpi Ng the Jewish Families Durning the War

| Irena Sendler | |

|---|---|

Sendler c. 1942 | |

| Born | Irena Krzyżanowska (1910-02-15)15 February 1910 Warsaw, Congress Poland |

| Died | 12 May 2008(2008-05-12) (aged 98) Warsaw, Poland |

| Occupation | Social worker, humanitarian, nurse, ambassador, educator |

| Spouse(s) | Mieczyslaw Sendler (1000. 1931; div. 1947) (m. 1961; div. 1971) Stefan Zgrzembski (m. 1947; died 1961) |

| Children | three |

| Parent(southward) | Stanisław Krzyżanowski Janina Karolina Grzybowska |

Irena Stanisława Sendler (née Krzyżanowska), besides referred to as Irena Sendlerowa in Poland, nom de guerre Jolanta (xv February 1910 – 12 May 2008),[i] was a Polish humanitarian, social worker, and nurse who served in the Polish Clandestine Resistance during World State of war 2 in German-occupied Warsaw. From Oct 1943 she was head of the children'southward section of Żegota,[2] the Smoothen Council to Aid Jews (Shine: Rada Pomocy Żydom).[3]

In the 1930s, Sendler conducted her social work as ane of the activists connected to the Gratuitous Smooth Academy. From 1935 to October 1943, she worked for the Department of Social Welfare and Public Health of the City of Warsaw. During the state of war she pursued conspiratorial activities, such as rescuing Jews, primarily as function of the network of workers and volunteers from that department, mostly women. Sendler participated, with dozens of others, in smuggling Jewish children out of the Warsaw Ghetto and then providing them with false identity documents and shelter with willing Polish families or in orphanages and other care facilities, including Catholic nun convents, saving those children from the Holocaust.[iv] [5]

The German occupiers suspected Sendler'south interest in the Polish Underground and in October 1943 she was arrested past the Gestapo, only she managed to hide the listing of the names and locations of the rescued Jewish children, preventing this information from falling into the hands of the Gestapo. Withstanding torture and imprisonment, Sendler never revealed anything well-nigh her work or the location of the saved children. She was sentenced to death just narrowly escaped on the day of her scheduled execution, later on Żegota bribed German officials to obtain her release.

In post-war communist Poland, Sendler continued her social activism but also pursued a government career. In 1965, she was recognised past the State of State of israel as Righteous Amidst the Nations.[half dozen] Among the many decorations Sendler received were the Gilded Cantankerous of Merit granted her in 1946 for the saving of Jews and the Order of the White Eagle, Poland'south highest laurels, awarded late in Sendler's life for her wartime humanitarian efforts.[a]

Biography

Before World State of war Two

Sendler was born on 15 February 1910 in Warsaw,[7] to Stanisław Henryk Krzyżanowski, a physician, and his wife, Janina Karolina (née Grzybowska).[eight] She was baptized Irena Stanisława on 2 February 1917 in Otwock.[9] She initially grew up in Otwock, a boondocks near 15 miles (24 km) southeast of Warsaw, where there was a Jewish community.[10] Her male parent, a humanitarian who treated the very poor, including Jews, gratuitous of charge,[xi] died in Feb 1917 from typhus contracted from his patients.[12] Subsequently his death, the Jewish customs offered fiscal help for the widow and her girl, though Janina Krzyżanowska declined their assistance.[8] [13] Afterward she lived in Tarczyn[14] and Piotrków Trybunalski.

From 1927, Sendler studied constabulary for two years and so Polish literature at the University of Warsaw, interrupting her studies for several years from 1932 to 1937.[8] [15] She opposed the ghetto benches organization practiced in the 1930s at many Polish institutions of higher learning (from 1937 at the University of Warsaw) and defaced the "non-Jewish" identification on her course carte du jour.[16] [17] [18] She reported having suffered from academic disciplinary measures because of her activities and reputation as a communist and philo-Semite. By the outbreak of Globe War Ii she submitted her magister degree thesis, but had not taken the final exams.[18] Sendler joined the Matrimony of Polish Democratic Youth (Związek Polskiej Młodzieży Demokratycznej) in 1928; during the war she became a member of the Polish Socialist Political party (PPS).[18] [nineteen] [20] She was repeatedly refused employment in the Warsaw school system considering of negative recommendations issued by the university, which ascribed radically leftist views to her.[15]

Sendler became associated with social and educational units of the Gratis Smoothen University (Wolna Wszechnica Polska), where she met and was influenced by activists from the illegal Communist Party of Poland. At Wszechnica Sendler belonged to a group of social workers led past Professor Helena Radlińska; a dozen or more women from that circumvolve would after appoint in rescuing Jews. From her social work on-site interviews Sendler recalled many cases of extreme poverty that she encountered among the Jewish population of Warsaw.[17] [21]

Sendler was employed in a legal counseling and social help clinic, the Section for Mother and Child Assistance at the Citizen Committee for Helping the Unemployed. She published two pieces in 1934, both concerned with the situation of children built-in out of spousal relationship and their mothers. She worked mostly in the field, crisscrossing Warsaw'southward impoverished neighborhoods, and her clients were helpless, socially disadvantaged women.[22] In 1935, the government abolished the section. Many of its members became employees of the City of Warsaw, including Sendler in the Section of Social Welfare and Public Health.[23]

Sendler married Mieczysław Sendler in 1931.[8] He was mobilized for state of war, captured equally a soldier in September 1939 and remained in a German language pw camp until 1945; they divorced in 1947.[24] [25] She then married Stefan Zgrzembski (born Adam Celnikier), a Jewish friend and wartime companion, by whom she had three children, Janina, Andrzej (who died in infancy), and Adam (who died of heart failure in 1999). In 1957 Zgrzembski left the family; he died in 1961 and Irena remarried her get-go husband, Mieczysław Sendler.[26] Ten years later they divorced over again.[27]

During World State of war 2

Annunciation of death penalty for Jews found outside the ghetto and for Poles helping Jews in whatever way, 1941

Soon afterward the German invasion, on ane Nov 1939, the German occupation authorities ordered Jews removed from the staff of the municipal Social Welfare Department where Sendler worked and barred the section from providing whatever assistance to Warsaw's Jewish citizens. Sendler with her colleagues and activists from the department's PPS jail cell became involved in helping the wounded and sick Polish soldiers. On Sendler'due south initiative the cell began generating false medical documents, needed by the soldiers and poor families to obtain aid. Her PPS comrades unaware, Sendler extended such assist as well to her Jewish charges, who were now officially served but by the Jewish customs institutions.[nineteen] With Jadwiga Piotrowska, Jadwiga Sałek-Deneko and Irena Schultz, Sendler also created other imitation references and pursued ingenious schemes in order to help Jewish families and children excluded from their section'south social welfare protection.[8] [19]

Effectually iv hundred thousand Jews were crowded into a small portion of the city designated every bit the Warsaw Ghetto and the Nazis sealed the surface area in Nov 1940.[28] As employees of the Social Welfare Department,[29] Sendler and Schultz gained admission to special permits for entering the ghetto to bank check for signs of typhus, a disease the Germans feared would spread beyond the ghetto.[30] [31] [28] Under the pretext of conducting germ-free inspections, they brought medications and cleanliness items and sneaked clothing, food, and other necessities into the ghetto. For Sendler, one initial motivation for the expanding ghetto assist performance were her friends, acquaintances and former colleagues who ended up on the Jewish side of the wall, outset with Adam Celnikier (he managed to leave the ghetto at the time of its liquidation).[28] Sendler and other social workers would eventually help the Jews who escaped or arrange for smuggling out babies and small children from the ghetto using various means available.[32] Transferring Jews out of the ghetto and facilitating their survival elsewhere became an urgent priority in the summer of 1942, at the time of the Bully Action.[33]

This work was done at huge risk, equally—since Oct 1941—giving whatever kind of assistance to Jews in German-occupied Poland was punishable by expiry, non but for the person who was providing the help but also for their entire family unit or household.[34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] [40] [41]

Sendler joined the Polish Socialists, a left-wing co-operative of the Polish Socialist Political party (PPS). The Polish Socialists evolved into the Shine Socialist Workers' Party (RPPS), which cooperated with the communist Polish Workers' Party (PPR). Sendler was known there by her conspiratorial pseudonym Klara and amongst her duties were searching for places to stay, issuing fake documents and being a liaison, guiding activists to hush-hush meetings. In the RPPS at that place were Poles she knew, involved in saving Jews, as well as Jews that she had helped. Sendler participated in the underground life of the ghetto. She described a commemoration event there, on the ceremony of the Oct Revolution but in the spirit of the Smoothen leftist tradition; it included creative performances by children.[20] While in the ghetto, she wore a Star of David equally a sign of solidarity with the Jewish people.[31]

The Jewish ghetto was a functioning community and to many Jews seemed the safest available identify for themselves and their children. In add-on, survival on the exterior was plausible simply for people with access to fiscal resources. This calculation lost its validity in July 1942, when the Germans proceeded with the liquidation of the ghetto in Warsaw, to be followed past the extermination of its residents. Sendler and her assembly—as related past Jonas Turkow—could take a small number of children, and a certain number could exist accepted and supported by Christian institutions, but a larger-scale activeness was prevented by the lack of funds. Initial funds for transfer and maintenance of ghetto children were provided by members of the Jewish community, withal in existence, in cooperation with women from the Welfare Department. Sendler and others, in accord with their mission, wanted to help the neediest children (such equally orphans) first. Turkow, who contacted Wanda Wyrobek and Sendler to take out of the ghetto and arrange care for his daughter Margarita, wanted to prioritize children of the most "deserving" (accomplished) people.[42]

During the Keen Action, Sendler kept entering or trying to enter the ghetto. She made desperate attempts to save her friends, just among her one-time Welfare Department associates unable or unwilling to leave the ghetto were Ewa Rechtman and Ala Gołąb-Grynberg. Co-ordinate to Jadwiga Piotrowska, who saved numerous Jewish children,[43] during the Groovy Action people from the Welfare Section operated individually (had no organization or leader). Other accounts suggest that women from that group concentrated on making arrangements for Jews who had already left the ghetto, and that Sendler in item took intendance of adults and adolescents.[42]

Żegota (the Council to Help Jews) was an underground organization that originated on 27 September 1942 every bit the Provisional Committee to Aid Jews, led past Zofia Kossak-Szczucka, a resistance fighter and writer.[17] [44] [45] Past that time, virtually Polish Jews were no longer alive. Żegota, established on 4 Dec 1942, was a new class of the committee, expanded by the participation of Jewish parties and chaired past Julian Grobelny.[45] It was financed by the founder of the Conditional Committee, the Regime Delegation for Poland, a Polish Underground State institution representing the Shine government-in-exile.[45] Working for Żegota from January 1943, Sendler functioned equally a coordinator of the Welfare Department network. They distributed money grants that became available from Żegota. Regular payments, however insufficient for the needs, enhanced their ability to assist the hiding Jews.[46] In 1963, Sendler specifically listed 29 people she worked with within the Żegota functioning, adding that xv more perished during the war.[47] In regard to the activity of saving Jewish children, according to a 1975 opinion written by Sendler'due south former Welfare Department co-workers, she was the nearly agile and organizationally gifted of participants.[42]

During the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, a network of emergency shelters was created by Sendler's group: private residencies where Jews could be temporarily housed, while Żegota worked on producing documents and finding longer-term locations for them. Many Jewish children went through the homes of Izabella Kuczkowska, Zofia Wędrychowska, and other social workers.[48] Helena Rybak and Jadwiga Koszutska were activists from the communist hole-and-corner.[49]

Every kid saved with my help is the justification of my existence on this World, and not a title to glory.

— Irena Sendler

In August 1943, Żegota fix up its children'southward section, directed by Aleksandra Dargiel, a manager in the Central Welfare Council (RGO). Dargiel, overwhelmed past her RGO duties, resigned in September and proposed Sendler to be her replacement. Sendler, then known by her nom de guerre Jolanta, took over the department from Oct 1943.[l]

Permanently, Jewish children were placed by Sendler'due south network with Smoothen families (25%), in Warsaw orphanage of the Franciscan Sisters of the Family of Mary led by Female parent Provincial Matylda Getter, Roman Catholic convents such every bit the Sister Servants of the Blest Virgin Mary in Turkowice (sisters Aniela Polechajłło and Antonina Manaszczuk) or the Felician Sisters, in Boduen Home charity facilities for children, and other orphanages (75%).[51] [52] A nun convent offered the best opportunity for a Jewish kid to survive and be taken care of. To accomplish the transfers and placement of children, Sendler worked closely with other volunteers.[44] [51] The children were oftentimes given Christian names and taught Christian prayers in instance they were tested.[53] Sendler wanted to preserve the children's Jewish identities, so she kept careful documentation listing their Christian names, given names, and current locations.[53] [b]

Co-ordinate to American historian Debórah Dwork, Sendler was the inspiration and the prime mover for the whole network that saved Jewish children.[54] She and her co-workers buried lists of the hidden children in jars in club to keep track of their original and new identities. The aim was to return the children to their original families, if yet alive after the state of war.[16]

Irena Sendler in December 1944

On xviii Oct 1943, Sendler was arrested by the Gestapo.[17] [55] As they ransacked her firm, Sendler tossed the lists of children to her friend Janina Grabowska, who hid the listing in her loose vesture.[53] [55] Should the Gestapo admission this information, all children would be compromised, only Grabowska was never searched. The Gestapo took Sendler to their headquarters and beat her brutally.[55] Despite this, she refused to betray any of her comrades or the children they rescued. She was placed in the Pawiak prison house, where she was subjected to further interrogations and beatings,[55] and from in that location on 13 November taken to another location, to be executed by firing team.[55] According to biographer Anna Mieszkowska and Sendler, these events took place on 20 January.[56] Her life was saved, however, considering the German guards escorting her were bribed, and she was released on the manner to the execution.[17] [31] [55] Sendler was freed due to the efforts of Maria Palester, a fellow Welfare Section activist, who obtained the necessary funds from Żegota master Julian Grobelny; she used her contacts and a teenage daughter to transfer the ransom money.[55] On xxx Nov, Warsaw'due south mayor Julian Kulski asked the German authorities for permission to re-employ Sendler in the Welfare Department with back-pay for the period of her imprisonment. Permission was granted on 14 Apr 1944, but Sendler found information technology prudent to remain in hiding, equally Klara Dąbrowska, a nurse.[57] Already in mid-December 1943, she resumed her duties equally manager of the children's section of Żegota.[58]

During the Warsaw Insurgence, Sendler worked every bit a nurse in a field hospital, where a number of Jews were subconscious among other patients. She was wounded by a German deserter she encountered while searching for food.[8] [59] She continued to piece of work equally a nurse until the Germans left Warsaw, retreating before the advancing Soviet troops.[viii]

After Globe State of war II

Sendler's infirmary, now at Okęcie, previously supported past Żegota, ran out of resources. She hitchhiked in armed forces trucks to Lublin, to obtain funding from the communist government established at that place, and then helped Maria Palester to reorganize the hospital equally the Warsaw'due south Children Home. Sendler also resumed other social work activities and quickly advanced within the new structures, in Dec 1945 becoming head of the Department of Social Welfare in Warsaw'south municipal government. She ran her department co-ordinate to concepts, radical at the time, that she had learned from Helena Radlińska at the Free University.[60]

Sendler and her co-workers gathered all of the records with the names and locations of the hidden Jewish children and gave them to their Żegota colleague Adolf Berman and his staff at the Central Commission of Polish Jews.[61] [62] Most all of the children's parents had been killed at the Treblinka extermination camp or had gone missing.[31] [8] Berman and Sendler both felt that the Jewish children should exist reunited with "their nation", but argued vehemently most specific aims and methods; most children were taken out of Poland.[62]

Over the years, amid Sendler's social and formal functions were a membership in Warsaw Urban center Council, chairmanships of the Committee for Widows and Orphans and of the Health Committee there, activity in the League of Women and in the managing councils of the Social club of Friends of Children and the Lodge for Lay Schools.[63]

Sendler joined the communist Smooth Workers' Party in January 1947 and remained a member of its successor, the Polish United Workers' Party, until the political party's dissolution in 1990.[64] According to the research done by Anna Bikont, in 1947 Sendler avant-garde to the party executive by condign a member of the Social Welfare Section at the Primal Committee'due south Social-Vocational Section. From then she continuously held a succession of loftier-level party and administrative posts during the entire Stalinist period and beyond, including the jobs of section director in the Ministry of Teaching from 1953 and of department director in the Ministry of Health in 1958–1962.[65] [66] Specially prior to 1950, Sendler was heavily involved in Primal Committee piece of work and party activism, which included implementation of social rules and propagation of ideas dictated past the Stalinist doctrine, and policy enforcement; by engaging in such pursuits, she abandoned some of her previously held views and lost some important acquaintances.[65] [67] After the autumn of communism, yet, Sendler claimed having been brutally interrogated in 1949 by the Ministry building of Public Security, defendant of hiding among her employees politically active former members of the Dwelling Regular army (AK), a resistance organization loyal during the state of war to the Polish government-in-exile.[17] [64] [65] [68] She attributed the premature birth of her son Andrzej, who did not survive, to such persecution.[viii] [12] Anna Bikont quoted Władysław Bartoszewski, who asserted before his death in 2022 that Sendler was not persecuted in communist Poland.[67] Her standing employment in high-level state positions likewise speaks confronting the possibility that she was a subject of serious investigation.[65] [b]

In the Polish People's Republic, Sendler received at to the lowest degree half-dozen decorations, including the Golden Cross of Merit (Złoty Krzyż Zasługi) for the wartime saving of Jews in 1946, some other Gilt Cross of Merit in 1956, and the Knight's Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta in 1963.[62] Materials dealing with her activities during the state of war were published,[27] [67] but Sendler became a well-known public personality only after being "rediscovered" by the grouping from an American high school in 2000 (at the historic period of 90).[69] She was recognized by Yad Vashem every bit one of the Smoothen Righteous Among the Nations and received her award at the embassy of State of israel in Warsaw in 1965, together with Irena Schultz.[31] [70] In 1983 she traveled to Israel, invited by Yad Vashem Constitute for the tree-planting ceremony.[viii] [71] [72] [seventy] [b]

From 1962, Sendler worked as deputy director in several Warsaw trade medical schools.[68] [73] At every stage of her career, she worked long hours and was intensely involved in diverse social work programs, such as helping teenage prostitutes in the ruins of postal service-war Warsaw recover and return to club, organizing a number of orphanages and intendance centers for children, families and the elderly, or a centre for prostitutes in Henryków. She was known for her effectiveness and displayed a sharp edge when confronted with obstruction or indifference.[68] [63]

Sendler's married man, Stefan Zgrzembski, never shared her enthusiasm for the mail service-1945 reality. Their union kept deteriorating. According to Janina Zgrzembska, their girl, neither parent paid much attention to the two children. Sendler was entirely consumed past her social work passion and career, at the expense of her own offspring, who were raised by a housekeeper.[74] [75] Around 1956, Sendler asked Teresa Körner, whom she had helped during the war and who was now in Israel, to assist her with clearing to Israel with children, who were Jewish and non rubber in Poland. Körner discouraged Sendler's move.[74]

In the leap of 1967, suffering from a variety of health problems, including a heart condition and anxiety disorder, Sendler applied for a disability alimony. She was dismissed from the schoolhouse's vice-principal position in May 1967, presently earlier the Arab–Israeli War.[76] From the fall of 1967, she continued working at the same schoolhouse as a teacher, manager of teacher workshops and librarian, until her 1983 retirement.[eight] [76] According to Sendler, in 1967 her daughter Janina was removed from the already published listing of students admitted to the Academy of Warsaw, simply Janina reported that she had merely failed to satisfy the admission requirements.[17] [76] The antisemitic campaign of 1967–68 in Poland left Sendler deeply traumatized.[76]

Sendler never told her children of the Jewish origin of their male parent; Janina Zgrzembska plant out as an adult. It wouldn't make any difference, she said: the way they were brought up, race or origin didn't matter.[77]

In 1980, Sendler joined the Solidarity movement.[viii] She lived in Warsaw for the balance of her life. She died on 12 May 2008, anile 98, and is buried in Warsaw'south Powązki Cemetery.[32] [78] [79]

Recognition and remembrance

Sendler with some people she saved as children, Warsaw, 2005

In 1965, Sendler was recognized by Yad Vashem as one of the Smoothen Righteous Amid the Nations.[a] In 1983 she was present when a tree was planted in her honor at the Garden of the Righteous Amidst the Nations.[80]

In 1991, Sendler was made an honorary citizen of Israel.[81] On 12 June 1996, she was awarded the Commander's Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta.[82] [83] She received a higher version of this honour, the Commander'south Cross with Star, on seven Nov 2001.[84]

Sendler's achievements were largely unknown in Due north America until 1999, when students at a loftier school in Uniontown, Kansas, led by their instructor Norman Conard, produced a play based on their inquiry into her life story, which they called Life in a Jar. The play was a surprising success, staged over 200 times in the Usa and abroad, and it significantly contributed to publicizing Sendler'due south story.[85] In March 2002, Temple B'nai Jehudah of Kansas Urban center presented Sendler, Conard, and the students who produced the play with its annual award "for contributions made to saving the world" (Tikkun olam honor). The play was adapted for goggle box as The Courageous Heart of Irena Sendler (2009), directed past John Kent Harrison, in which Sendler was portrayed past actress Anna Paquin.[86] [87]

In 2003, Pope John Paul II sent Sendler a personal alphabetic character praising her wartime efforts.[88] [89] On 10 Nov 2003, she received the Order of the White Eagle, Poland's highest noncombatant ornament,[xc] and the Shine-American laurels, the January Karski Accolade "For Courage and Heart", given past the American Center of Shine Culture in Washington, D.C.[91]

In 2006, Polish NGOs Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej and Stowarzyszenie Dzieci Holocaustu, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland, and the Life in a Jar Foundation established the Irena Sendler's Honour "For Repairing the World" (pl:Nagroda imienia Ireny Sendlerowej "Za naprawianie świata"), awarded to Smooth and American teachers.[92] [93] The Life in a Jar Foundation is a foundation dedicated to promoting the attitude and message of Irena Sendler.[93]

On 14 March 2007, Sendler was honoured by the Senate of Poland,[94] and a year after, on 30 July, by the United states of america Congress. On eleven April 2007, she received the Order of the Smile; at that time, she was the oldest recipient of the award.[95] [96] In 2007 she became an honorary citizen of the cities of Warsaw and Tarczyn.[97]

Posthumously

In April 2009 Sendler was posthumously granted the Humanitarian of the Twelvemonth award from The Sis Rose Thering Endowment,[98] and in May 2009, Sendler was posthumously granted the Audrey Hepburn Humanitarian Award.[99]

Effectually this time American filmmaker Mary Skinner filmed a documentary, Irena Sendler, In the Name of Their Mothers (Smooth: Dzieci Ireny Sendlerowej), featuring the last interviews Sendler gave before her death. The moving picture made its national U.S. broadcast premiere through KQED Presents on PBS in May 2011 in honor of Holocaust Remembrance Day[100] and went on to receive several awards, including the 2012 Gracie Award for outstanding public television documentaries.[101]

In 2010 a memorial plaque commemorating Sendler was added to the wall of 2 Pawińskiego Street in Warsaw – a edifice in which she worked from 1932 to 1935. In 2022 she was honoured with another memorial plaque at 6 Ludwiki Street, where she lived from the 1930s to 1943.[102] Several schools in Poland have also been named later her.[103]

In 2013 the walkway in front of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw was named subsequently Sendler.[104]

In 2016, a permanent exhibit was established to honor Sendler'southward life at the Lowell Milken Middle for Unsung Heroes museum, in Fort Scott, KS.[105]

Gal Gadot has been bandage to play Sendler in a historic thriller written by Justine Juel Gillmer and produced by Airplane pilot Moving ridge.[106]

On February 15, 2020, Google celebrated her 110th birthday with a Google Doodle.[107]

In 2022 a statue of her in Newark, Nottinghamshire, was announced.[108]

Literature

In 2010, Polish historian Anna Mieszkowska wrote a biography Irena Sendler: Mother of the Children of the Holocaust.[109] In 2011, Jack Mayer tells the story of the four Kansas school girls and their discovery of Irena Sendler in his novel Life in a Jar: The Irena Sendler Project.[103]

In 2016, Irena'south Children, a volume near Sendler written by Tilar J. Mazzeo, was released by Simon & Schuster. A version adjusted to be read by children was created past Mary Cronk Farell.[110] The young reader'south edition was named as a notable volume for older readers past the Sydney Taylor Book Award.[111] Another children's picture volume titled Jars of Hope: How 1 Woman Helped Save 2,500 Children During the Holocaust, is written by Jennifer Roy and illustrated past Meg Owenson.

Sendlerowa. West ukryciu ('Sendler: In Hiding'), a biography and book nearly the people and events related to Sendler'due south wartime activities, was written by Anna Bikont and published in 2017. The book received the 2022 Ryszard Kapuściński Award for Literary Reportage.

Gallery

-

Irena Sendler'south tree on the Avenue of the Righteous at Yad Vashem in Israel

-

Irena Sendler's funeral, May 2008

-

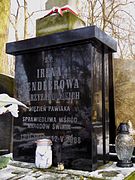

The headstone on Irena Sendler's grave

-

A memorial plaque on the wall of 2 Pawińskiego Street in Warsaw

-

Irena Sendler Avenue

Encounter besides

- The Holocaust in Poland

- Rescue of Jews past Poles during the Holocaust

- Polish Righteous Among the Nations

- List of Poles: Holocaust resisters

- Individuals and groups profitable Jews during the Holocaust

- Henryk Sławik

Notes

a. ^ Sendler was i of the first Poles recognized as Righteous Amid the Nations due to the efforts of Jonas Turkow, who stated for a Shine language periodical in State of israel: "This noble adult female ... worked for Żegota and saved hundreds of Jewish children, placing them in orphanages, convents and other places".[112] The number of Jewish children saved through Sendler'south efforts is not known. The Social Welfare Department of the Central Commission of Smooth Jews stated in Jan 1947 that Sendler saved at least several dozen Jewish children.[113] Later in her life, Sendler repeatedly claimed that she had saved two,500 Jewish children. When Michał Głowiński, who as a child survived the state of war with Sendler's help, was working on his book The Black Seasons in the late 1990s, Sendler insisted that he wrote nigh the two,500 children she saved. Equally Głowiński later told Anna Bikont, he felt obliged to comply because "1 cannot reject Sendler". Sendler ofttimes spoke of the list of 2,500 children she produced, kept in two bottles and gave to Adolf Berman, but no such list has ever materialized and Berman never mentioned its existence.[114] For the first time she talked almost the list and the 2,500 saved children (and adults) in 1979; dorsum and so, however, she did not propose that she was personally responsible for their survival and named twenty-four people too involved in their rescue.[115]

b. ^ Actual events tend to exist difficult to reconstruct because afterward, purposely or inadvertently, for different audiences and at different times, Sendler told unlike stories with aspects that were mutually incompatible or contrary to known facts.[51] For example, in 1998 Sendler claimed that the communist authorities kept refusing to issue her passport for 20 years, despite the invitations from Yad Vashem she had been receiving during that period. Anna Bikont found those claims to be false. The passport was refused in 1981, after the commencement such invitation, considering of the lack of diplomatic relations with Israel, and the conclusion was reversed in 1983. Previously Sendler as well had a passport: on several occasions she went to Sweden to visit her son, who was receiving medical handling there.[116]

References

- ^ Irena Sendler. An unsung heroine. Lest We Forget. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Mordecai Paldiel, The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust, Ktav Publishing House (January 1993), ISBN 0-88125-376-half-dozen

- ^ I'grand no hero, says woman who saved two,500 ghetto children xv March 2007 www.theguardian.com accessed 21 September 2020

- ^ Baczynska, Gabriela (12 May 2008). Jon Boyle (ed.). "Sendler, savior of Warsaw Ghetto children, dies". Reuters . Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ^ "Rethinking the Polish Undercover". Yeshiva University News.

- ^ Atwood, Kathryn (2011). Women Heroes of World War Two. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. p. 48. ISBN9781556529610.

- ^ "Facts most Irena — Life in a Jar". Retrieved 29 Baronial 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Polscy Sprawiedliwi – Przywracanie Pamięci". sprawiedliwi.org.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ Bikont, Anna, Sendlerowa, p. 51

- ^ "Irena Sendler — Rescuer of the Children of Warsaw". www.chabad.org . Retrieved 29 Baronial 2016.

- ^ Joshua D. Zimmerman (2015). The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939–1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 304. ISBN9781107014268.

- ^ a b "Biografia Ireny Sendlerowej". tak.opole.pl (in Shine). Zespół Szkół TAK im. Ireny Sendlerowej.

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 55–56

- ^ "Aleja Ireny Sendlerowej". Dzielnica Śródmieście one thousand. st. Warszawy (in Smoothen). Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ a b Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. sixty–61

- ^ a b Staff writer (22 May 2008), The Economist obituary. Retrieved 8 Apr 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Magdalena Grochowska (12 May 2008), "Lista Sendlerowej – reportaż z 2001 roku" (The Sendler listing – newspaper report from 2001) at DzieciHolocaustu.org.pl. See likewise: Lista Sendlerowej at Gazeta Wyborcza (subscription required). Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 65–69

- ^ a b c Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 71–75

- ^ a b Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 84–86

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 61–62

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 52–55

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, p. 64

- ^ Anna Mieszkowska (January 2011). Irena Sendler: Mother of the Children of the Holocaust. Praeger. p. 26. ISBN978-0-313-38593-3.

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 70–71

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 307–308

- ^ a b Bikont, Sendlerowa, p. 311

- ^ a b c Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 75–84

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, p. 20

- ^ Richard Z. Chesnoff, "The Other Schindlers: Steven Spielberg's epic flick focuses on merely one of many unsung heroes" (annal), U.S. News and World Report, 13 March 1994.

- ^ a b c d e "Irena Sendler". Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ a b Monika Scislowska, Associated Printing Writer (12 May 2008). "Polish Holocaust hero dies at age 98". Usa Today . Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 90–91

- ^ Kurek, Ewa (1997). Your Life is Worth Mine: How Polish Nuns Saved Hundreds of Jewish Children in High german-occupied Poland, 1939-1945. Hippocrene Books. ISBN9780781804097.

- ^ Kadar, Marlene (31 July 2015). Working Memory: Women and Piece of work in World War II. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. ISBN9781771120364.

- ^ Zamoyski, Adam (2009). Poland: A History. Harper Press. ISBN9780007282753.

- ^ Zamoyski, Adam (2009). Poland: A History. Harper Printing. ISBN9780007282753.

- ^ Baker, Catherine (18 Nov 2016). Gender in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe and the USSR. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN9781137528049.

- ^ Deák, István; Gross, Jan T.; Judt, Tony (6 Nov 2009). The Politics of Retribution in Europe: World War 2 and Its Aftermath. Princeton Academy Press. ISBN978-1400832057.

- ^ Piotrowski, Tadeusz (1998). Poland's Holocaust: Indigenous Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947. McFarland. ISBN9780786403714.

- ^ Tomaszewski, Irene; Werbowski, Tecia (2010). Code Proper noun Żegota: Rescuing Jews in Occupied Poland, 1942-1945 : the Almost Dangerous Conspiracy in Wartime Europe. ABC-CLIO. ISBN9780313383915.

- ^ a b c Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 92–108

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 155–168

- ^ a b Mordecai Paldiel "Churches and the Holocaust: unholy teaching, good samaritans, and reconciliation" pp. 209–x, KTAV Publishing House, Inc., 2006, ISBN 978-0-88125-908-7

- ^ a b c Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 135–139

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 139–143

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, p. 309

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 152–154

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 172–199

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 214–219

- ^ a b c Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 109–133

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 144–145

- ^ a b c Atwood, Kathryn (2011). Women Heroes of World War II. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. p. 46. ISBN9781556529610.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis (13 May 2008). "Irena Sendler, Lifeline to Young Jews, Is Dead at 98". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 Apr 2015.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 219–226

- ^ Mieszkowska, Anna (2014). Prawdziwa Historia Ireny Sendlerowej. Warszawa: Marginesy. ISBN978-83-64700-58-3.

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 230–232

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 243–246

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 249–254

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 274–279

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, p. 12

- ^ a b c Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 271, 280–284

- ^ a b Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 284–286

- ^ a b Olga Wróbel, Bikont: Na każdym kroku pilnie wykluczano Żydów z polskiej społeczności ('Bikont: The Jews were diligently excluded from Polish society at every step'). 2 February 2018. Bikont: Na każdym kroku. Krytyka Polityczna. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 290–300

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, p. 308

- ^ a b c Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 379–381

- ^ a b c "Sendler Irena – WIEM, darmowa encyklopedia" (in Polish). PortalWiedzy.onet.pl. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 365–368

- ^ a b Bikont, Sendlerowa, p. 310

- ^ "Irena Sendler, who saved 2,500 Jews from Holocaust, dies at 98". Haaretz . Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "The Story of Irena Sendler (Feb 15, 1910 — May 12, 2008)". Taube Philanthropies. [Also in:] "Laurels named for Righteous Gentile". European Jewish Congress. 2 June 2008. Archived from the original on 26 August 2022 – via Net Archive.

- ^ "She was a mother to the whole world – girl of Irena Sendler speaks" [To była matka całego świata – córka Ireny Sendler opowiedziała nam o swojej mamie] (in Polish). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 298–307

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, p. 335

- ^ a b c d Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 312–318

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, p. 325

- ^ "Irena Stanisława Sendler (1910–2008) – dzieje.pl" (in Polish). Retrieved 27 Apr 2015.

- ^ David M. Dastych (16 May 2008). "Irena Sendler: Pity and Backbone". CanadaFreePress.com. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ Zawadzka, Maria. "TREES OF IRENA SENDLER AND January KARSKI IN THE GARDEN OF THE RIGHTEOUS". Shine Righteous. POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ "Irena Sendler". Jewish Virtual Library. American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE). Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ .P. 1996 nr 58 poz. 538, citation: "za pełną poświęcenia i ofiarności postawę w niesienui pomocy dzieciom żydowskim oraz za działalnośċ spoleczną i zawodową" (Smoothen)

- ^ "Krzyz Komandorski Orderu Odrodzenia Polski..." (in Polish). Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ K.P. 2002 nr 3 poz. 55, citation: "w uznanui wybitnych zasług w nieseniu pomocy potrzebującym" (Polish)

- ^ "Nigh the Projection – Life in a Jar". Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ The Mettlesome Middle of Irena Sendler at CBS.com Archived 21 July 2012 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ Richard Maurer (ram-30) (19 Apr 2009). "The Courageous Eye of Irena Sendler (Boob tube Movie 2009)". IMDb.

- ^ "List Papieża practice Ireny Sendler [Letter of the alphabet of the Pope to Irena Sendler]". wyborcza.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ Scott T. Allison; George R. Goethals (2011). Heroes: What They Do and Why We Demand Them. Oxford University Printing. p. 24. ISBN978-0-nineteen-973974-5.

- ^ One thousand.P. 2004 nr xiii poz. 212, citation: "za bohaterstwo i niezwykłą odwagę, za szczególne zasługi w ratowaniu życia ludzkiego" ("for heroism and extraordinary courage, for outstanding merits in saving homo lives") (Smooth)

- ^ Warszawa, Grupa. "The Association of "Children of the Holocaust" in Poland". www.dzieciholocaustu.org.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Opis konkursu". Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Polscy Sprawiedliwi – Przywracanie Pamięci". www.sprawiedliwi.org.pl (in Smooth). Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ Wyszyński, Kuba. "Irena Sendler nie żyje". www.jewish.org.pl (in Smooth). Archived from the original on 25 Jan 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "IRENA SENDLEROWA Kawalerem Orderun Uśmiechu". OrderUsmiechu.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Nagroda im. Ireny Sendlerowej". NagrodaIrenySendlerowej.pl (in Smooth). Retrieved 27 Apr 2015.

- ^ Tarczyn official website (2017), "Irena Sendler." Honorary citizen, lived in Tarczyn before the invasion.

- ^ Smolen, Courtney (six April 2009). "Executive Director of NJ Commission on Holocaust Education to Bestow Honorary Award to CSE Professor, April 19". NJ.com . Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ "Irena Sendler awarded the Audrey Hepburn Humanitarian Award". www.audrey1.org . Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "PBS National Premiere of IRENA SENDLER In the Proper name of Their Mothers on May 1st, National Holocaust Remembrance Twenty-four hour period". KQED's Pressroom.

- ^ "SF-Krakow Sister Cities Association – Irena Sendler Documentary Movie Wins 2012 Gracie Honor". world wide web.sfkrakow.org . Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Odsłonięto tablicę upamiętniającą Irenę Sendlerową" (in Polish). Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ a b "About the Project". Life in a Jar: The Irena Sendler Project . Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ "Aleja Ireny Sendlerowej, Honorowej Obywatelki m.st. Warszawy". www.radawarszawy.um.warszawa.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on ten November 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Lowell Milken Center for Unsung Heroes - Freedom's Frontier National Heritage Expanse". Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ "Gal Gadot Will Play This Real-Life Holocaust Hero Who Rescued Jewish Children". Kveller. sixteen Oct 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ "Irena Sendlerowa's 110th Birthday". Google. 15 Feb 2020.

- ^ "Newark statue for WW2 Polish woman who saved hundreds". BBC News. 26 June 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ Mieszkowska, Anna (27 September 2014). "Prawdziwa historia Ireny Sendlerowej". Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ "Iii Twice-told stories". Toronto Star, 12 November 2016, page E22.

- ^ "Sydney Taylor Book Honour" (PDF). Clan of Jewish Libraries. Retrieved 11 Nov 2021.

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 13–fourteen

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, p. 287

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 403–407

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 399–401

- ^ Bikont, Sendlerowa, pp. 327–329, 338–340

Bibliography

- Anna Bikont, Sendlerowa. W ukryciu ('Sendler: In Hiding'), Wydawnictwo Czarne, Wołowiec 2017, ISBN 978-83-8049-609-5

- Yitta Halberstam & Judith Leventhal, Small Miracles of the Holocaust, The Lyons Press; 1st edition (13 Baronial 2008), ISBN 978-i-59921-407-viii

- Richard Lukas, Forgotten Survivors: Polish Christians Remember the Nazi Occupation ISBN 978-0-7006-1350-2

- Anna Mieszkowska, IRENA SENDLER Mother of the Holocaust Children Publisher: Praeger; Tra edition (eighteen November 2010) Language: English ISBN 978-0-313-38593-3

- Mordecai Paldiel, The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust, Ktav Publishing House (Jan 1993), ISBN 9780881253764

- Irene Tomaszewski & Tecia Werblowski, Zegota: The Council to Assist Jews in Occupied Poland 1942–1945, Toll-Patterson, ISBN 1-896881-xv-seven

External links

- Irena Sendler: In the Name of Their Mothers (PBS documentary, first aired May 2011)

- Irena Sendler – Righteous Among the Nations – Yad Vashem

- Irena Sendlerowa on History'southward Heroes – Illustrated story and timeline.

- Life in a Jar: The Irena Sendler Project

- Irena Krzyżanowska Sendler at Detect a Grave

- Snopes discussion of an electronic mail regarding the Nobel Prize

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irena_Sendler

0 Response to "What Was Gies Motivation for Helpi Ng the Jewish Families Durning the War"

Post a Comment